I once failed at a job interview because, according to the

feedback from the HR manager (who was not part of the interview panel) I hadn’t

exhibited enough ‘passion’ for the post. I pointed out that the job description

hadn’t asked for passion. I thought they wanted: the right qualifications (tick), experience in a similar role (tick), proven competence (tick) etc. etc. etc. (tick,tick, tick). The HR manager was polite and sympathetic, but that wasn’t enough to manufacture up a job for me. At least she ensured my expenses were paid promptly. I’d like to say the rejection was the making of me, but it was a considerable disappointment at the time.

It wouldn’t have got me the job, but I wish I’d know then what the etymology of passion is. I might have been able to point out that passion

has not always been something that would prove an asset in the work place, or a way to market one’s services.

Passioun, came into English in the thirteenth century, via Classical Latin, Old French and Anglo Norman. Its original meaning was physical suffering, and it was used initially in this country to mean any kind of suffering. The references were often in relation to the suffering of Jesus and the Christian martyrs, and the meaning of passion in this sense lingers on to this day. Hence, we instinctively understand what Bach intends us to feel when listening to his oratorios – the St Matthew’s Passion and St

John’s Passion.

During the 1400s, passion started to mean a painful disorder or physical ailment. A couple of centuries later it could mean strong emotion too. By the seventeenth century it acquired sexual connotations. Milton wrote of ‘wanton passions’ in Paradise Lost, and in the early twentieth century DH Lawrence has one of his heroines in Sons and Lovers troubled by a lover’s ‘yearning’ passion.

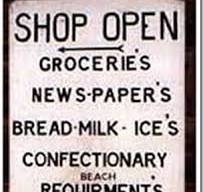

The Oxford English Dictionary records the adjective passionate as meaning ‘susceptible or readily swayed by passions or strong emotions, easily moved to strong feeling, of changeable mood, volatile.’ I’m not sure too many employers really want a work force made up of moody and volatile employees – I understand just getting some to turn up rather than WFH (work from home) can be a challenge these days – but maybe I’m out of touch.

Passion is still strong in the advertising world. Look at all those restaurants who advertise themselves as ‘cooking with passion’ and florists for whom ‘flowers are my life’s passion’ Even a barber who markets himself as ‘passionate about hair.’ Which doesn’t sound very safe to me.

Links to my books and social media

You can find all my books and short stories on

Amazon books.

At least one story always free. ALL BOOKS FREE ON

KINDLE UNLIMITED

www.amazon.co.uk/-/e/B00RVO1BHO fb.me/margaretegrot.writer